The vital role clinical supervision plays in the FNP programme

Lindsay Andrews, Clinical Quality Lead - Safeguarding and Supervision, FNP National Unit

2020 promises to be a year of exciting new developments for FNP on several levels. For sites this will mean implementing a new, more personalised approach to programme delivery. There will also be the design and launch of a new FNP Information System for collecting and analysing programme data. For the FNP National Unit, there will be a move to a new home within the Nursery and Midwifery Directorate of Public Heath England.

However, one key area that remains firmly in place as a constant and stabilising factor throughout these changes will be the core model element of supervision in FNP. Supervision is a fundamental and essential component of the FNP programme. It takes the form of weekly one-to-one supervision meetings between the supervisor and family nurse, fortnightly case-based presentation meetings, and supervisor-accompanied home visits every four months, supported by reflective practice.

These all serve to support effective quality improvement for family nurses, FNP supervisors and site teams as a whole. Crucially, the FNP model of supervision and oversight incorporates and encourages active reflection, which further deepens and drives understanding, and underpins a process of continual improvement in programme quality, service delivery and client outcomes. This supervisory approach is also mirrored in the therapeutic relationship between nurse and mother.

An international review of reflective practice in NFP was undertaken in 2019 (NFP Reflective Supervision: Project Report). A number of family nurses and supervisors from FNP in England contributed to this important review which highlighted the strong culture of supervision in FNP teams in England. The review also provided us with the opportunity to rationalise our supervision documentation which is due for release in April 2020.

The review reiterated the fact that well-led FNP teams create a culture of excellence and mutual support by developing a reflective and open approach to the analysis of the teams’ work. Examples of insight and learning are also shared between FNP sites through blogs, case studies and forums on an online platform, FNP Online, and through FNP National Unit training events and informal local networks of FNP sites. The review identified the power of reflection as a potent tool that enables learning from experience in that it helps the family nurse to:

• Understand what it is she already knows (individual learning)

• Identify what else she needs to know in order to advance understanding of her role and work (contextual learning)

• Make sense of new information/learning and feedback in the context of her experience of her role and work (relational learning)

• Guide choices for further learning about the role and work of the family nurse (developmental learning).

Family nurses undertake complex work to assess clients, plan visits and provide effective interventions, and each of these elements are supported through reflection as a teaching and learning tool with supervision providing space to both explore and contain any feelings of concern or anxiety.

At the very first NFP trial site of Elmira, New York, the team identified a need for structured support to sustain them in work that was isolating and often emotionally draining. To this day, a significant function of supervision is that it pays due care and attention to the emotional weight of the work, seeking to prevent burnout and compassion fatigue amongst nurses – thus sustaining resilience at individual and team level.

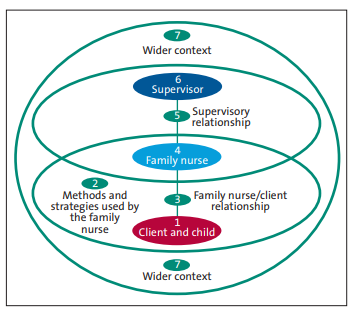

Seven Eyed Model, Hawkins and Shohet

Since its inception in 2007 FNP in England has deployed the Seven Eyed Model by Hawkins and Shohet (authors of Supervision in the Helping Professions, 4th edition) to support all aspects and provides a useful model for supervision. The Seven Eyed Model (watch short video) complements the Kolb Learning Cycle (watch short video).

The integration of both facilitative reflection and analysis of:

1. The lived experience of infant/client;

2. The tools and working approaches of the FNP programme;

3. The nature/quality of the client-FNP nurse relationship;

4. The family nurse’s therapeutic use of self and her own state;

5. The quality of the FNP supervisor and family nurse relationship;

6. The FNP supervisor’s therapeutic use of self and her own state;

7. And, finally, the wider contextual factors that enable or hinder implementation of FNP programme delivery.

The FNP National Unit surveys FNP sites quarterly on all aspects of clinical practice including supervision and uses survey data to continually learn and improve supervision in FNP. This iterative learning was an important factor in the effective implementation of Personalisation as part of the FNP ADAPT project.

Further reading: International Journal of Birth & Parent Education; Winter 2015/2016, Vol. 3 Issue 2 p25-28, 4p (subscriber log in required)

Follow Lindsay on twitter @Lindsandrews66