It takes awareness, courage and compassion to overcome the effect of parental ACEs on child socio-emotional development

Andreea Moise, Principal Quality Improvement Analyst at the Family Nurse Partnership National Unit

Since the original Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study conducted in the United States in 1998 1, extensive research has continued to reveal how ACEs affect health later in life as well as the well-being of those experiencing them 2. However, most research on the effects of exposure to ACEs conducted to date has focused on health outcomes in adulthood for the same individuals. Therefore, much less is known about the potential intergenerational effect, such as parental exposure to ACEs and impact on child development.

The assumption that parents’ and children’s lives are interdependent is consistent with the Life Course Theory 3, one of the theories that underpins the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) programme. Therefore, ACEs are considered as form of disadvantage that may be experienced across generations, a fact also supported by empirical research.

Throughout the FNP programme, family nurses provide a safe space for young mothers to explore stressful or traumatic experiences, such as being abused or neglected. It takes courage to have these difficult conversations and awareness to make sense of these experiences and the potential consequences for these women and their babies.

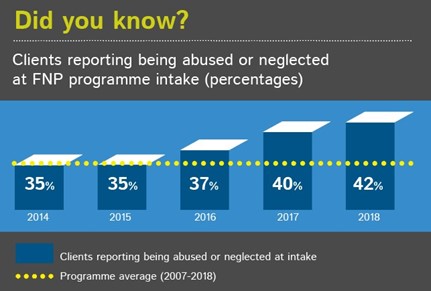

Since 2007, around 35% of all FNP clients reported abuse or neglect at the point of joining the programme. We have seen a gradual increase in the last five years, reaching 42% of clients enrolled in 2018 who reported abuse and neglect. There could be multiple reasons or a combination of reasons driving this upward trend; an increase in vulnerability of the target population; the nursing workforce advancing their skills in developing trusting relationship with clients and even an increase around the social acceptability of sharing these experiences.

Of particular interest in recent studies, has been the relationship between maternal ACEs and children’s socio-emotional development. These studies found that parental ACEs can be detrimental to early child socio-emotional development 4–8. Most commonly, parental ACEs can affect children through parenting behaviour - parents who experienced early traumatic events generally have an increased risk of social, emotional, and physical health problems. These may then translate into lower levels of social functioning and increased reactivity to stress affecting their ability to engage in positive parenting.

Exploring ACE’s as part of the care offered, in a non-judgmental manner provides a platform for early intervention and home visiting programs to work with families to increase strengths and reduce the impact of adverse experiences on their children. Without intervention, these problems are likely to persist further affecting children later in life and potentially leading to poorer health and health behaviours, lower psychological wellbeing, educational performance and earnings, as evidenced by many studies.

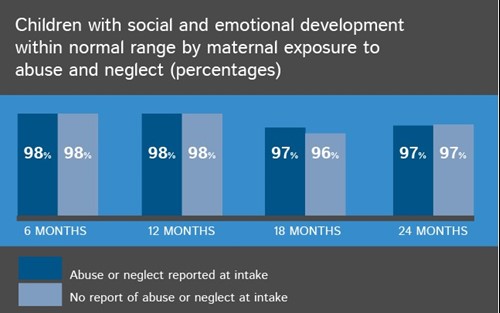

A glimpse of our programme data shows us that children whose parents have a history of abuse and neglect have similar socio-emotional development to children from less disadvantaged parents. This finding potentially reassures us that there is no indication of intergenerational transmission of disadvantage as a result of the evidence-based work of family nurses.

And what could be more rewarding for a parent who experienced adversities, than seeing their child reach their potential?

Although the evidence on which particular programmes work to reduce the prevalence of ACEs is still limited, home visiting programmes have been classed as promising for preventing child maltreatment. As well as being effective in tackling risk factors such as household adversities. This is further proven by then FNP programme achieving the highest score for evidence of a long-term positive impact on child outcomes according to the Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook.

While learning about parents’ exposure to adversities alone has the potential to contribute to a better understanding of the context in which child development takes places, exploring child development in that context is also necessary; in order to prevent the transmission of adversity and inequality across generations and improve life course outcomes for children and their families.

But there is a question I have been reflecting on – “How can each and every one of us help make a difference?” The silver lining is that ACEs do not define who somebody is, or who they can become. The least we can do is to foster resilience by offering our compassionate support to our friends, family members, neighbours and even complete strangers in the face of adversity.

Endnote:

Socio-emotional development of children is assessed using the Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ: SE-2) at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months during the duration of the FNP programme.

References:

1 Felitti, Vincent J., Anda, Robert F., Nordenberg, Dale, Williamson, David F., et al. (1998) ‘Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study’. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), pp. 245–58.

2 Allen, Matilda and Donkin, Angela (2015) The impact of adverse experiences in the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects, London. [online] Available from: http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/the-impact-of-adverse-experiences-in-the-home-on-children-and-young-people/impact-of-adverse-experiences-in-the-home.pdf

3 Elder, Glen H (1998) ‘The life course as developmental theory’. Child Development, 69(1), pp. 1–12.

4 Folger, Alonzo T., Eismann, Emily A., Stephenson, Nicole B., Shapiro, Robert A., et al. (2018) ‘Parental Adverse Childhood Experiences and Offspring Development at 2 Years of Age’. Pediatrics, 141(4), pp. 1–11.

5 Madigan, Sheri, Wade, Mark, Plamondon, Andre and Jenkins, Jennifer (2015) ‘Maternal abuse history, postpartum depression, and parenting: Links with preschoolers’ internalizing problems’. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(2), pp. 146–156.

6 Madigan, Sheri, Wade, Mark, Plamondon, Andre, Maguire, Jonathon L. and Jenkins, Jennifer M. (2017) ‘Maternal Adverse Childhood Experience and Infant Health: Biomedical and Psychosocial Risks as Intermediary Mechanisms’. Journal of Pediatrics, 187, pp. 282–289.

7 McDonnell, Christina G. and Valentino, Kristin (2016) ‘Intergenerational Effects of Childhood Trauma: Evaluating Pathways Among Maternal ACEs, Perinatal Depressive Symptoms, and Infant Outcomes’. Child Maltreatment, 21(4), pp. 317–326.

8 Treat, Amy E., Sheffield-Morris, Amanda, Williamson, Amy C. and Hays-Grudo, Jennifer (2019) ‘Adverse childhood experiences and young children’s social and emotional development: the role of maternal depression, self-efficacy, and social support’. Early Child Development and Care, pp. 1–15.